I did mention my changing opinion though, and in truth this is a film I’ve come to love. I’ve thought about why and it comes down to this – if a project is made with real love, a sincere effort to create something great via its production values, a plot that aims for some degree of profundity and the sheer abilities of the talent involved then I’m more than fine with that. You don’t hire Robert Wise to direct if you don’t care. Ditto Alan Dean Foster on writing duties, and a score by Jerry Goldsmith that really touches the heavens – it’s gorgeous. The Motion Picture looks great (the effects have been ‘touched up’ to make it look more 21st century, though in an unobtrusive way rather than garishly), and credit goes to the acting, especially William Shatner, who conveys his character’s human fallibility so well and completely looks the part.

I don’t think the film can ever be thought of as a blast, as a fast-paced adventure yarn, but taken on its own merits it’s a brilliant work all told, and worthy of re-appraisal. I think there are better entries in the series, but many try to capture a degree of fun and dramatic weightlessness that this one bypasses, aiming instead for thoughtful science fiction, living up to the story’s remit of space exploration and discovering new life forms, which it ends up pulling off to fine effect.

The second entry in the series is now considered such a success that it’s hard to remember the tough times involved in getting the thing made. First the budget, with Khan having less than a quarter of The Motion Picture’s money invested in it. You can see that on the screen occasionally, from some of the effects work to shots from the first film that have simply been recycled. Gene Roddenberry, blamed for The Motion Picture’s relative lack of success, was kicked off having any direct involvement in this project, Khan being handed to producer Harve Bennett and Nicholas Meyer (the young director who at the time was best known for Time After Time, one of those forgotten movies that really deserves better). The pair was hired to deliver a film that could be made on a fraction of the original’s budget, and between them came up with perhaps the best and certainly the most exhilarating entry in the entire series.

Khan’s a lot of fun, and if you want to judge its impact on the franchise, let alone its wild profitability, then consider there might not have been future films nor The Next Generation without it, while the recent, rebooted movies have been made with this one’s spirit in mind. It achieves a very fine balance between action adventure and a story carrying some heft, ruminating on the theme of Kirk’s advancing age and casting Ricardo Montalban’s revenge obsessed Khan as a future Captain Ahab, locked in his own version of Moby Dick (he even quotes passages from Melville’s text) with Kirk his whale. Considering the combatants never meet in person, their duel taking place entirely over ship to ship communication, their enmity produces pure electricity. Throw in a sub-plot involving Genesis, the sci-fi device that can somehow create new Earths from lifeless planets, and you have an outright winner. Leonard Nimoy famously wanted to make this film his swansong as Spock, part of what feels like a perpetual struggle to move beyond the pointy ears. As it happened, he had such a good time making the film that he agreed to stay on, not only helping to dictate the future plotline of the series but relegating Saavik to a lesser role. Kirstie Alley’s feisty Vulcan cadet was initially intended to replace Spock and enjoyed enhanced screen time, killing off most of the cast in the opening scene’s teaser that turns out to be a training exercise, but Nimoy’s decision to return put paid to her future development.

Khan remains a real blast of a picture, even more than 35 years down the line. It’s certainly good enough to make any update of it redundant, a fact that would be unfortunately ignored in the future.

Read the full review

Star Trek III: The Search for Spock (1984)

All systems automated and ready. A chimpanzee and two trainees could run her.

The base rule about Star Trek movies is that the even numbered ones are good, the odd numbered poor. I would argue this entry provides an exception to the rule (which was completely thrown out by the time the Next Generation crew took over). Leonard Nimoy, excited about his time on The Wrath of Khan decided he wished to return and took over directorial duties after Nicholas Meyer left the project. Harve Bennett turned in a script that padded out the film’s fairly rudimentary plot (I mean come on, they were always going to find Spock!) by taking the ultimate fan servicing step of destroying the Enterprise itself. There’s a great Klingon villain, played by a pre-Doc Brown Christopher Lloyd, and the Federation are outed as overly bureaucratic and short-sighted.

The theme for Kirk is one of giving up everything for the sake of saving his best friend. The Captain’s son dies. His career is ruined, his ship in pieces over the equally devastated Genesis world. It’s a heavy price to pay and thank goodness it’s worth it as he goes through the wringer in achieving his goal. The Enterprise’s theft and escape from space dock, involving the old crew foiling the pursuit of the allegedly superior Excelsior, is staged with bravura, while the tussle against Kruge’s (Lloyd) Bird of Prey is impressive and echoes some of the previous film’s best moments. The script also has space for an injection of humour, which Nimoy directs well, along with giving everyone in the crew something to do. On the downside, the film’s budgetary limitations are shown up from time to time, visual reminders of the fact it cost less than half of the year before’s Return of the Jedi to make. The stuff in space is fine enough with ILM producing the goods and conjuring a dramatic detonating Enterprise, but the footage on the Genesis planet very clearly takes place on a sound stage, matte paintings to give a sense of depth looking like exactly what they are.

For all its limitations, The Search for Spock is a worthy entry, confidently helmed by Nimoy (no mean feat for a debut turn behind the camera) and showcasing a rather beautiful score by James Horner. Recommended.

Read the full review

Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home (1986)

They like you very much, but they are not the hell your whales

The premise for the crew’s fourth outing wasn’t especially promising. An intergalactic Swiss Roll turns up to threaten the Earth’s atmosphere, its message unidentifiable and making the planet’s destruction an inevitability. The only ones who can help are the Enterprise crew, by now flying a Klingon Bird of Prey and returning to Earth to face justice for their transgressions during the previous movie. Working out that the Roll’s noises are in fact whale calls, said mammals being extinct in their time, the only course of action they can take is to fly back into the past, find two humpbacked whales, and somehow return them to the future. Sounds silly, right? Not to mention overly polemical about environmental issues (which were emerging globally as the big deal back in the mid-eighties), and that’s before we explore the practicalities. Apparently, time travel can be achieved by sling-shotting around the sun at warp speed, and you can imagine the writers’ meeting where that one was pitched – yeah, it’ll do…

And yet it works, it works really well, largely because the film plays up to its comic potential with a cast that’s prepared to take itself not at all seriously. One of the main criticisms of the ‘lazier’ Trek movies is that beyond the Holy Trinity of Kirk, Spock and McCoy the rest of the crew just kind of stands around and watches, and that doesn’t happen here as everyone gets a significant sub-plot of their own. There’s the delicious sight of Chekov asking passing San Franciscans where the ‘nuclear wessels‘ are in a thick Russian accent. Scottie loses it with a computer that he has to operate using the keyboard rather than talking to it. Best of all is Bones’s visit to a hospital, emitting a series of complaints about primitive techniques – ‘My God man, drilling holes in his head is not the answer!‘ Amidst all this the potentially heavy handed message about humanity’s folly in not protecting the environment is managed carefully and touched upon as lightly as possible. The whales are for the most part animatronic models, and I couldn’t tell, and I’ve watched this entry many times. It’s all directed with great confidence and aplomb by Leonard Nimony, who gives his own character some of the best lines (Spock discovers swearing on 20th century Earth – ‘The hell they did‘) while ensuring the whole crew gets more or less equal billing.

Star Trek IV was a box office hit, well received by the critics, and ensured the series’ longevity. What could have been a dull tubthumper turns out to be one of the most entertaining entries in the franchise, a genuinely fun and wholesome attempt to show the possibilities inherent within the Trek universe.

Star Trek V: The Final Frontier (1989)

What does God need with a starship?

By some distance the least appreciated of the ‘Original Series’ films, Star Trek V reads like an extended ego massage for its star and on this occasion director, William Shatner. The premise is that Kirk defeats God, which leads to some very easy criticisms of the Captain, by all accounts no stranger to arrogance and hubris (though it’s worth arguing that many of his appearances, especially on the likes of Boston Legal, play up to his image and suggest a level of self-awareness for which he has not always been credited). And that’s only the start of the film’s problems. Limited budgets were ever a problem during the 1980s run, but it’s only here that Star Trek actually looks cheap, much of the effects work struggling to match the movie’s ambition. And certain scenes just jar. There’s the jaw-dropping moment when Uhura performs a feather dance to distract some guards, which spits in the face of narrative logic, the feline bar dancer with three breasts, the Klingon captain pursuing the Enterprise who’s ultimately dealt with as a very naughty boy…

For all that, it isn’t without worth. The film spends some time taking a deep breath as its characters go on vacation, and the campfire scenes between Kirk, Spock and McCoy are warmly handled, just three dudes chilling out. The main story, in which Spock’s half-brother – who’s ruled by his emotions – methodically takes over the Enterprise via a combination of mind control and faith techniques, provides some good material and effectively alienates the main cast members from the rest of the crew. We get to explore some of the reasons why McCoy is as jaded and cynical as he’s become, which is really well directed, nicely acted by DeForest Kelley and carries emotional weight. But these moments are distractions from a plot that largely disappoints, especially at the climax, and too often the film relies on weak humour, as though Shatner wanted to reprise the comic tone of The Voyage Home but didn’t have the material nor the ‘fish out of water’ basis that made that previous instalment such a winner. Worst of all perhaps is the decision to relegate the Klingons to secondary characters, a sideline threat, a mistake that would not be repeated in the series’ next instalment.

These problems were reflected in a relatively poor (though not disastrous) return at the box office, and it remains the worst reviewed of the entire franchise, according to Rotten Tomatoes. Fair? Personally I’m not sure, though there’s little arguing with the episode’s status as the weak link within a very strong field.

Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country (1991)

Must have been your lifelong ambition

The existence of a sixth big screen outing hung in the balance for a time, concerns over the poor returns for The Final Frontier and the now rapidly advancing age of the cast suggesting the original crew had enjoyed their last star trek. But the increasing success on television of The Next Generation made the project feasible, and once Nicholas Meyer was installed as director there was a growing sense of all becoming right with the world again. Scouring the known universe for a plot, they did what any good Western used to do and turned real-life events into the backdrop for a story, this time the collapse of the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc, translated here into the end of the Klingon Empire as a military threat after the destruction of their main energy source. Against the better wishes of anyone with peace on their mind, Kirk and his crew are dispatched to escort the Klingon Chancellor to Earth in order to begin talks about ending hostilities. Disaster ensues when the Chancellor is murdered and his ship fired upon, apparently by the Enterprise, which leads to Kirk and McCoy being tried and found guilty of murder. They know they didn’t do it and so do we, and so a desperate bid for escape takes place before further assassinations can take place and war is resumed.

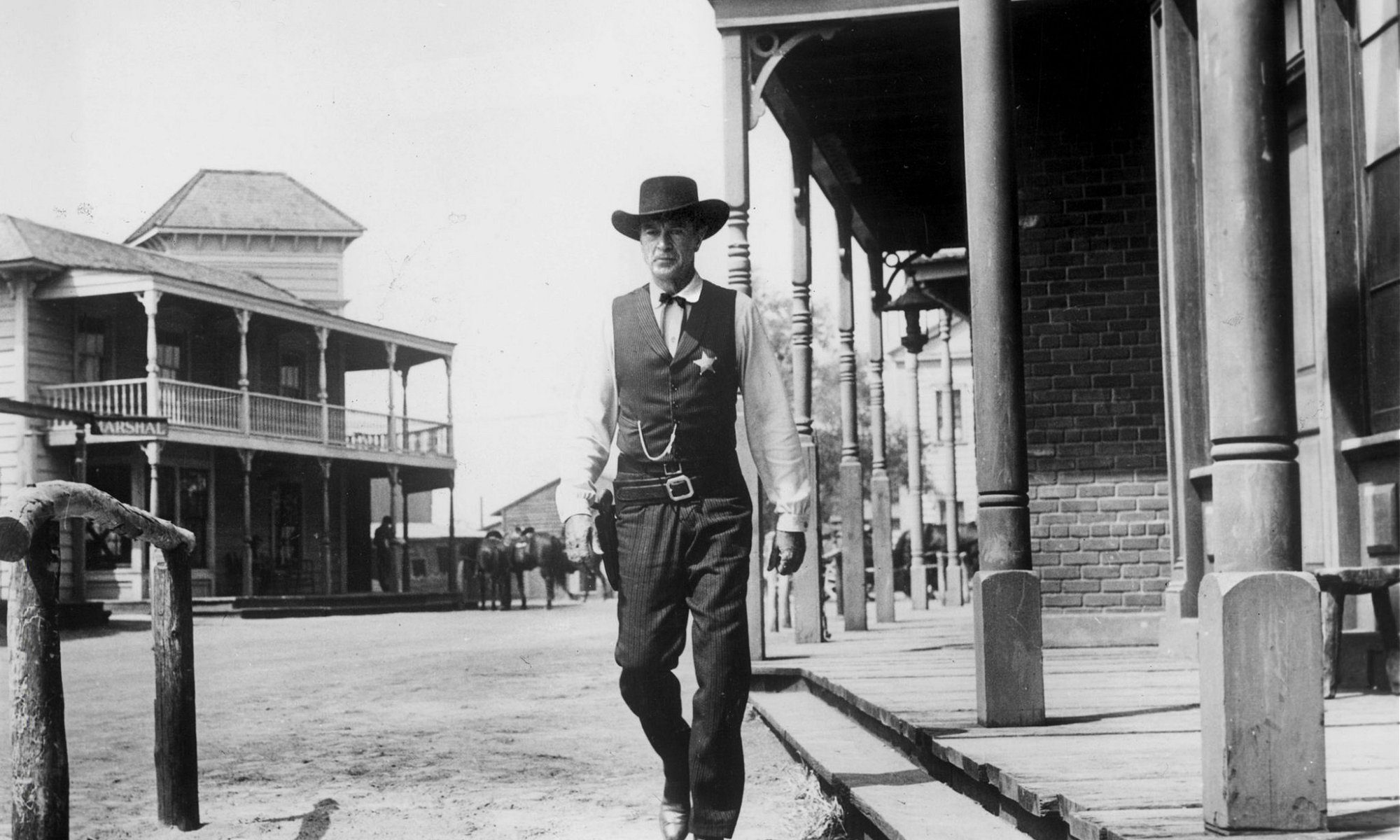

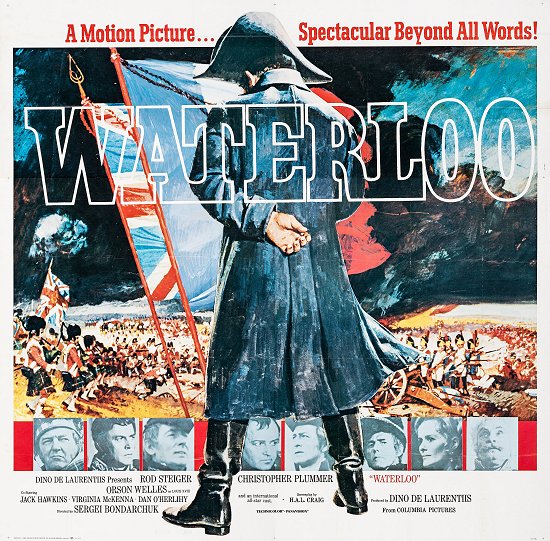

The Undiscovered Country turns out to be a fine end to the crew from the Original Series, packed with wit and adventure and ever poking fun at the players’ ages, their status as defunct warriors in a new era of intergalactic Glasnost. It has a good pace, especially when the film focuses on Kirk and McCoy’s stay at a dismal frozen prison camp and their action packed efforts to get away. The Enterprise plays host to a compelling Whodunnit mystery, Spock leading the investigation, alongside Kim Cattrall as a young Vulcan officer. David Warner features briefly as the slain Ambassador, but the most fun is to be had from Christopher Plummer, almost unrecognisable as a Shakespeare quoting Klingon war veteran, ever with a thin smile on his face as he deals happily in death and destruction.

The costs for this one were trimmed considerably as Paramount ruminated over the film’s potential box office. An original budget of $41 million was cut back to $27 million over the course of production, the cast taking pay cuts and lavishly developed scenes being simply excised from the script. That makes The Undiscovered Country one of the series’ cheaper entries, far less costly than The Motion Picture from thirteen years beforehand, and yet it never really matters. Meyer uses humour, pace and characterisation in place of expensive special effects, building to a good natured ending point that places a nice seal on the old crew’s antics.

Star Trek: Generations (1994)

It was… fun. Oh my…

If there’s an entry in the series that has me disagreeing with the general consensus, then it’s Generations. I think it’s fascinating. The Nexus ribbon that forms the film’s object is a really interesting idea and it’s very nicely played out, giving Patrick Stewart the kind of emotive material to work with that he so rarely got and in any event being the kind of entity you can imagine people fighting to enter, hence Malcolm McDowell’s scientist, obsessed to the point of psychosis in returning there. The movie exists as a handing over of the baton from Kirk to Picard and the Next Generation crew, and it almost entirely works, from the former’s unease over the ceremonial duties he has to perform through to the fateful decision he makes to work alongside his successor in stopping McDowell’s mad scientist. For Kirk it’s a fitting send-off, letting him go down as a man of action, as having made a difference, even if for fans it felt like a death happening too easily. All this can make me overlook the film’s plot holes, of which there are many. If you were Jean-Luc and you could have returned to any time in reality, would you have chosen the moment he did…?

In other places, Generations doesn’t work quite so well and perhaps it’s here that the film’s troubled production comes into sharper focus. Fighting budgetary restraints and relying often on the TV production crew, the film sometimes looks like an expanded episode of the series rather than a big screen feature, with several scenes thrown in – notably the crash landing of the Enterprise’s saucer section on a forested world – to lend a little cinematic gloss to the proceedings. Worse still is the forced humour deriving from Data’s decision to have his emotion chip fitted, the shtick relying on the viewer’s willingness to find hilarity in the character’s tics and cheap gags. I wasn’t willing. It stunk.

Whether through the novelty of seeing two Trek captains in the same film, goodwill from audiences or the fact it’s actually not a bad film (the effects too look to have taken an upward shift, thanks to improved technology and despite the limited costs), Generations was a box office success and ensured further entries for the series. Personally, it’s one I’ve always rather liked.

Star Trek: First Contact (1996)

You broke your little ships

The Borg, huh? Sound Swedish, and they remain one of my favourite villains in Science Fiction, I think because their hive mind and lack of emotional involvement make them the stuff of sweaty nightmares. I remember watching the old Next Generation two-parter, The Best of Both Worlds, the delirious anticipation between the the third series’ close and the start of the next – how could they leave things the way they did at the end of Season 3? What a cliffhanger! In many ways, the decision to give the Borg an individual ruler in First Contact comes across as a shame. Despite a fine turn from Alice Krige, the Queen’s existence flies into the face of the species’ many ranks of anonymous servers somewhat, the idea you could kill millions of them and they would just keep on coming.

The film was a big success and it stands for me as a high point in the series, easily the best of the Next Generation movies with a fast-paced plot designed for the big screen and never fails to entertain. It’s also a two-hander, Stewart’s beleaguered Captain tussling with the Borg on board the Enterprise while Ryker leads a team on Earth of the past aiding James Cromwell’s grizzled Zefram Cochran to achieve ‘first contact’, the legendary moment of humanity’s future history when warp speed is first achieved. The latter serves up some choice moments as Cochran, this revered historical figure, turns out to be a drunk who sees only profit in his advancements, but the film wholly belongs to Patrick Stewart. Burdened with memories of his past encounter with the Borg, Picard transforms their efforts to take over the Enterprise as a personal crusade, the script offering clever allusions between his battle and that of Captain Ahab, not the first time Star Trek would refer to Moby Dick but very effectively done. Data gets a decent slice of the action as the crew member who spends his time with Krige’s unnaturally sexy Queen, giving him more to do than react to stuff happening as in Generations.

It’s a confident directorial outing for Jonathan Frakes, who prior to this had helmed a number of TV episodes but was given his debut cinematic job on First Contact. He opts for an action adventure playing at breakneck pace, which is good because the sheer speed at which things happen obscure the film’s various illogical twists and turns, the plotholes that can occur when a story messes around with timelines. More than one viewing ensures these are exposed, but they don’t detract from what is a cracking couple of hours’ entertainment, arguably drilling down the ‘science’ of some Star Trek entries but optimising instead on fun and spectacle, which is no bad thing.

Star Trek: Insurrection (1998)

I kiss you and you say “yuck”?

Insurrection stands as one of those great missed opportunities for me. After First Contact goodwill in the franchise was high. The series could have gone anywhere, done anything. A direct sequel might have been in order, but instead it was decided to make something in the vein of the fourth outing, an episode light in tone that could find favour with audiences in the same way that the ‘one with the whales’ had done. Jonathan Frakes’s services as director were retained, and Michael Piller, responsible in part for creating Deep Space Nine as well as many of the Next Generation’s highest regarded scripts, wrote the screenplay.

The result is a film that, while never really bad, plays like an extended TV episode rather than a bold cinematic outing. The story, about a planet with rings that contain some life rejuvenating properties and is contested over, is quite a decent one, leading to the crew members regaining elements of their youth. These range from the nice – La Forge no longer requiring his visor – to the rather less edifying sight of Riker getting some sex scenes with Troi. Just put it away, Number One! The early plotline during which Data appears to turn rogue is good, largely because it shows the potential for the series’ ubiquitous android as a villain, albeit temporarily. And the film offers roles for two fine actors – Anthony Zerbe plays a Federation Admiral who has dubious morals, while no less a figure than F Murray Abraham is on hand as a bad guy who is more or less unrecognisable thanks to his character undergoing perpetual face stretching operations in order to stay alive.

As an episode in the TV series, Insurrection would have been fine. It isn’t boring and the scenes in space – by now, CGI was used entirely for these bits and offered up some rather ravishing spacescapes – are fluid and exciting. But it just doesn’t have the dramatic heft and scope of a feature film. The humour doesn’t really work for anyone not overtly familiar with the characters and perhaps, in the end, unlike their original series counterparts the Next Generation was unable to transfer so successfully to the big screen.

Star Trek: Nemesis (2002)

You’re too slow, old man

There comes a point watching Star Trek movies, specifically those that transfer a crew seen on TV onto the big screen, where you have to wonder what the point of it all is. What do they do to make the adventures more cinematic? Where in the film is the justification for making fans part with their money to see their heroes at a multiplex? The movies featuring the original cast got that, I think, whether serving up visuals that TV budgets could never aspire to creating or using directors and crews with skills honed in producing for the cinema. Even The Final Frontier, for all its deep flaws, and they’re deep indeed, had a level of scale and ambition that made it appropriate for movie audiences. Contrast that with an entry like Nemesis, and the previous Insurrection, and all that goes away. As does much in terms of characterisation here. There’s about a third of the film’s footage that was excised from it as they focused on moments of character interaction, the aim being to present a trim, lean action movie that captured the spirit of The Wrath of Khan with its opposing captains being the driving force.

The result is a largely incoherent mess, one that wastes the potential of a riveting plot that pits Picard against a clone of himself, played here by a young Tom Hardy. Hardy plays Shinzon, created by the Romulans as a version of Picard to be used as a spy but is instead confined to slavery, before he emerges in adulthood as the leader of the Remans (the second class subordinates to Romulus). Instigating a coup over the Romulan Empire, Shinzon lures the Enterprise to meet him as part of a plot to capture Picard and use his blood in an effort to stop his own rapid ageing. But things don’t go to plan; the Captain smells a rat, especially when he learns that Shinzon’s real intention is to invade the Federation using a new super weapon. Sounds well enough, yet it’s wasted due to a staggering level of indifference from all concerned. Action scenes are inserted for no good reason, such as the exploration of a planet using dune buggies, which doesn’t make any sense and is just done to insert an artificial sense of urgency. A prototype version of Data is discovered seemingly for comic effect (it isn’t funny), and to give the character an ‘out’ when he sacrifices himself at the end of the film. There’s a subplot involving the marriage of Riker and Troi, which only works at all because of the actors’ chemistry, while the space scenes feature some gorgeous CGI but have no dramatic heft. They’re there to make us go ‘ooh pretty‘ rather than mattering. Even the scene when the Enterprise rams Shinzon’s ship lacks weight; we’ve seen worse happen and the moment doesn’t have any real consequences for where the story’s heading towards. Jerry Goldsmith, hired once again the provide the music, doesn’t really offer anything new. Like everyone else, he isn’t trying. As for the cut footage, we’re talking potentially about some of the series’ best bits, the little interactions that make us care for these characters. Without them, why should we be interested?

Sad then, to see the franchise go out – as indeed it was about to on TV schedules as Enterprise disappointed towards cancellation – with such a tired sigh. At its best, Star Trek could be both thrilling and smart, was capable of depicting a crew presented with problems with which they dealt intelligently, just as you imagine a group of humans given the best and most optimistic vision of the future doing, but here it just feels like everyone had had enough. Nemesis should have been a final hurrah to the franchise; instead it’s a death knell.

Star Trek (2009)

Green-blooded hobgoblin

Sometimes you just have to judge a film based on how much fun you had watching it at the cinema, and I admit I had a blast with the rebooted Star Trek. As a long-term sort of fan (having seen all the films, many of the TV shows, not having a clue about the Klingon language and missing half the fan-servicing references) I was sceptical about this one. Given the semi-successful nature of cinematic relaunches, the spate of which we’re undergoing still, I was worried that Star Trek would turn out to be a quick buck-making bit of nonsense, and so it was pleasing to enjoy it as much as I did.

J J Abrams has his fans and detractors, but he knows how to inject pace and generate excitement. There’s a great Red Letter Media video that goes on at some length about everything that’s wrong with the Star Wars prequels. Lots of walking and talking, no sense of urgency, and the contrast is made with this one, characters who seem to spend their lives running around in blind panic, everything cut to enhance the frantic action, and not only does it play splendidly it can make viewers overlook the nonsensical plot, how fragile it all holds together. It’s certainly a lot of fun. The young cast bring a great deal of energy to their roles, and apart from Karl Urban’s hysterical impression of DeForest Kelley do a lot to enhance their famous characters. A note on Chris Pine’s Kirk, played here as a wisecracking superhero and displaying none of the vulnerability Shatner went for in his big screen outings. It’s fascinating to watch Kirk’s rise from cheeky outcast to ship’s captain, while the fan servicing scene in which he beats Spock’s Kobayashi Maru simulation is bravura storytelling, telling you everything you need to know about both characters.

The question remains whether it’s actually Star Trek at all. I guess it’s a reboot for people who got a ride out of the Transformers movies, mixing high velocity action with nods and allusions to its sources. It’s better than those films too because Abrams has enough respect for the material to make it worthwhile. Is it up to the standard of the original series of movies? Not sure about that, and there’s an element of pointlessness about trying to compare films made in the 1980s with those for twenty first century audiences – different films for different viewers – but, as mentioned above, I had a great deal of fun watching it, and that counts for a lot.

Star Trek Into Darkness (2013)

I’m going to make this very simple for you

Given the success of the 2009 relaunched Star Trek, was it the best idea to recycle a much loved character and storyline from earlier in the series for the sequel? For the first half of Into Darkness it all works well enough. Kirk and the Enterprise wilfully break the Prime Directive in rescuing Spock (seasoned viewers will be smiling at the sheer number of times this impossible rule has been shattered previously), and they’re then tasked with getting rid of a mysterious figure who’s been sabotaging the Federation. It’s only when this man is revealed to be none other than Khan Noonien Singh that the plot unravels into a retread of The Wrath of Khan, even rehashing the death of a major character in saving the ship and the frustrated bellow of ‘KHAAAAANNNNN!’.

There’s an extent to which all this is very nice, multiple winks to long term viewers – hey look kids, it’s just like before but a bit different – and entertaining action adventure for the casuals. Benedict Cumberbatch as Khan is about as good as Benedict Cumberbatch as Khan is likely to be, in fact he’s great – composed, cold and brilliant where Montalban was all bombast and spat out curses. The plotline that has a Starfleet Admiral (played, in a great bit of casting, by Peter Weller) using both Khan and Kirk as pawns within a scheme to spark off a war against the Klingons, is pretty good stuff. And the movie runs at a suitably frantic pace, as before packed with sufficient action to stop all but the most jaded audience members unpicking the nonsensical logic and plot-holes.

On the downside, in a universe that could have gone anywhere the decision to supply a rebooted franchise with a rebooted plot smacks of laziness and feels a bit unnecessary. Was there any need for any of it? Did Cumberbatch’s Khan do a number on Montalban? Did you burn your copy of Wrath of Khan because it was simply done better and ‘right’ this time around? Of course not. Where Kirk’s anger over Khan’s actions in the earlier film held real weight, the culmination of mounting frustration, when Spock does the same here it just feels contrived, present as a nod for the fans. Similarly the sacrifice Kirk makes in his one, echoing Spock’s actions earlier in the series, carries little heft because the film has already posited an ‘out’ for his character, a means to bring him back to life, whereas Spock’s death way back in the early 1980s was emotionally devastating due to its (apparent) finality. No amount of Simon Pegg’s Scotty cheering up the screen or Alice Eve appearing solely for the scene where she strips off (for virtually no reason) can mask the emptiness at the heart of this film, the fact it was made because it could be, for the money, and that’s a shame.

Star Trek Beyond (2016)

In Loving Memory of Leonard Nimoy

The most recent Trek movie has been tinged with tragedy. First there was the passing of Leonard Nimoy, the legendary actor without whom the series just feels a bit less, indeed it was his cameo appearances in the two previous entries that lent them an indefinable amount of credibility and continuity. And then there was the tragic loss of Anton Yelchin, just 27 years old and already with a fine catalogue of appearances hinting at a great screen acting career in prospect. For this film, J J Abrams had jumped over to some other relaunched science fiction epic, staying on as producer only, and the reins were handed over to Justin Lin, the genius behind those loud, brash and disposable Fast and Furious movies. The signs were ominous. Would Beyond turn into a sequence of elaborate set piece action sequences linked with superfluous plot points?

The answer, happily, is no, and I would argue that for the first time in the rebooted series there’s a sense of these films having the conviction to go their own way rather than endlessly reference their own past (though it’s filled with nods all the same, with special mention for allusions to Star Trek: Enterprise). The worst thing I can say about Beyond is that Idris Elba makes for a surprisingly weak villain, but that’s more or less okay because the rest clicks into place really well. The entire crew gets significant parts to play, including Simon Pegg’s Scotty (surely just a coincidence that Pegg co-wrote the screenplay), and Sofia Bouletta’s alien warrior makes for an agreeable addition to the cast. It moves along at the usual breakneck pace and some of the visuals are astonishing, in particular Starbase Yorktown, which shows a level of care and attention to stretching the limits of the human imagination in a science fiction setting.

On the downside, the entire effort seems to be on offering spectacle at the expense of anything close to science; it’s fine enough as a pure fantasy, yet when you think of what they aimed to make with The Motion Picture all those years ago you realise that the premise’s initial intentions have been pretty much trodden underfoot. Does Beyond, therefore, do anything that you can’t get with the rebooted Star Wars series, for example, or perhaps more pertinently Guardians of the Galaxy, which was already stealing this franchise’s thunder. Once those elements linking the Star Trek universe with scientific possibilities have been expunged, does anything remain that’s special or unique, or is this just another blockbuster property swimming to keep up with the rest?

Who knows? More instalments are promised, with no less a figure than Quentin Tarantino linked at some point in the future, and in the meantime a new series has been commissioned by CBS, which has attracted mixed reviews but, speaking personally, I rather enjoyed it. The existing movies pretty much span my lifetime, with the original series released beforehand and many additional Star Trek shows on television occurring in the intervening years. All told I find it a mixed bag, some genuinely great ideas colliding with the occasional plodding storytelling and dull characters. And yet its central thesis, of a future in which the world has combined its collective powers and set out to explore the universe, is a very encouraging, fascinating and ultimately optimistic one. As I write these words it seems a very long way away, whether the last gasp of old, deep rooted values or something fundamentally unsavoury at the heart of the human condition, but for me the vision of mankind’s destiny that Star Trek posits is about as hopeful as these things can ever get, and there’s nothing very wrong in watching that.