This is a brief return to the site, because I was asked to take part in the Christopher Plummer Blogathon and had to say yes. After all, the Canadian enjoyed such a long and varied career. IMDb credits him with more than two-hundred acting appearances, stretching from the mid-1950s right through to his passing in 2021. He was always in demand, always gave his best, and even in certain films that weren’t very good, was ever capable of being great in them. I can’t imagine there are many people who don’t have a movie that featured him in their lists of favourites.

But what to cover here? There are some truly great performances, which for me includes his brilliantly nuanced Sherlock Holmes in Murder by Decree. You want to see the ordinarily cold and emotionally isolated great detective explode in righteous anger? Here’s the place to do it. We could also talk about his good work in less than stellar pictures – he was a memorable Aristotle in Oliver Stone’s flawed, watchable Alexander, and I love his gleefully villainous turn in Dragnet. I’m also a fan of The Assassination of Sarajevo, a Yugoslavian film about the murder of Archduke Franz Ferdinand that kicked off World War One. Plummer plays the Austrian Archduke, a remote, aloof aristocrat who isn’t necessarily a bad person, yet has absolutely no interest in or connection with the people over whom he rules.

The choice comes down to two personal favourites, incidentally a pair of movies that cost fortunes to make and gained notorious reputations for failing at the box office and ruining their production companies. One is The Fall of the Roman Empire, the 1964 epic that was eventually remade as the more visceral and far less thoughtful Gladiator years later. Despite the latter’s Oscar wins and financial success, I will always maintain the earlier film is superior. Plummer gets the choice role of the Emperor Commodus, playing someone credited by the movie as precipitating ‘the Fall’, as a study in megalomaniac madness. He looks like he’s having a great time doing so, and he is by some distance the best thing in it. You can read my extensive thoughts on it here.

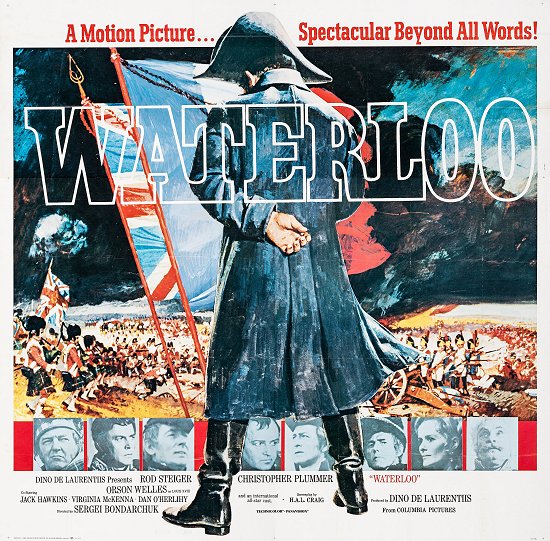

That leaves the other pick, which is 1970’s Waterloo, a regular watch for me that extends back to a brief period back in my teens when I joined in with a group of wargamers. If it does nothing else, then Waterloo makes an attempt to recreate a full-scale Napoleonic battle by near enough recreating a full-scale Napoleonic battle. The film features an army of extras, literally an army in fact, as the Russian production company Mosfilm invested in the project, contributing a sizeable cash injection and thousands of soldiers (between 17,000 and 20,000, according to sources) from the Soviet army. The Belgian field of battle was replicated in Ukraine, with the topography worked upon, fields sown and buildings constructed to historical specifications. Underground piping was installed to help muddy the terrain. Endless numbers of costumes were designed to fit the fighting cast into either British, French or Prussian troops, according to the filming schedule of the day.

Waterloo covers the period at the end of the brief and violent Napoleonic era. It opens with the French Emperor being forced to abdicate, his return from exile on the island of Elba and recapture of the French throne, and the short campaign that led to his final defeat on the eponymous battlefield. He is played by Rod Steiger, and he’s the film’s main focus. Steiger puts in a shouty performance, playing Napoleon as a middle-aged man riddled with sickness and on the verge of a nervous breakdown. He’s used to being the cleverest guy in the room, but he’s never faced a British army under the Duke of Wellington’s command, and not knowing exactly what he will face at Waterloo rattles him.

Plummer is Arthur Wellesley, the lordly supreme commander of Britain’s forces, which are the first to face Napoleon upon his return due to being stationed in Belgium at the time. Although he was not the first choice to play the Iron Duke (Peter O’Toole and Michael Caine were under consideration), he turns out to be a characteristically great piece of casting. The real Wellington was renowned for his haughty demeanour, an aristocrat who publicly referred to his soldiers as scum, yet pragmatic in battle and extremely charismatic as a commander. Plummer gets it, turning his work into little less than extracting the actual Duke from the past and into the film. While I rather like Hugh Fraser’s portrayal in the Sharpe series, this is pretty much definitive. Wellington lives again.

After an hour of preamble, the film’s main set-piece is its recreation of Waterloo, effectively a war-game battle played with human beings rather than little models. If anyone ever wants to see how these things happened without the convenience of being able to travel to the period, then this is as good as it will ever get. Napoleon’s objective is to defeat the British before they can be relieved by the Prussian army, which is approaching the field of battle. Time is not on his side. Rain the previous day has made conditions less than perfect, and all Wellington needs to do is hold his position, delay the French until Field Marshall Blucher (Sergo Zakariadze) arrives with his black-uniformed Germans. This, however, is asking a lot. Despite his advancing years and illness, Napoleon is renowned as the premier commander of his time, bringing an uncanny knack for probing and teasing the enemy until he finds a weak spot and exploits it. Two critical holding positions for Britain are the farmhouse at La Haye Saint and the chateau at Hougoumont, from which he needs to dislodge them, and these two locations become the focus of the fighting.

Sure enough, having softened the British up with artillery barrages, Napoleon begins sending in the troops, blocks of blue-coated men in close formation who are being sent to their deaths. When a unit is ordered into battle, they are heralded by marching band music; I was surprised to learn that the tunes chosen by the film are pretty much historically accurate, as is the nature of the fighting itself. The first rows of men are decimated by musket fire, before they make it to close-quarter tussling and deadly bayonets become the main weapons. The battle progresses elsewhere, as the 70,000 strong French army slowly presses against and breaks the lines of their opposition. It becomes clear that Napoleon is on the brink of winning, however it’s really a race against time as, at a certain point, he realises the Prussians are close to relieving their British allies.

As a re-enacted battle from history, Waterloo does a fine job. Its attention to detail is so absolute that there’s little for nit-pickers to complain about beyond tiny changes made by the film, along with a dramatic intention to turn the ebb and flow of battle into a knife-edged contest of wills. On the whole, it’s an impressive effort. Certain moments, such as the film’s depiction of the charge of the Scots Greys heavy cavalry, are so well done that it recreates, almost perfectly, Elizabeth Thompson’s famous painting, Scotland Forever!, on the screen. Key instances, like the decision of the French Marshall Ney (Dan O’Herlihy) to instigate a mass cavalry advance of his own when he believes the British are retreating, is also shown, leading to one of the film’s more visually rich sequences as aerial shots depict horsemen riding into units of soldiers, all fighting for their lives.

We all know how Waterloo ended, of course, and its final moments are played out as a British victory, an exhausted Napoleon exiting the field in disgrace as he knows he’s finally run out of road. The battle was a close run thing, and was executed in bloody fashion, claiming the lives of close to 50,000 men, including many of Wellington’s generals and his closest staff members. Eyewitness accounts put many of the Duke’s actual quotes from the occasion into Plummer’s script, recreating his haughty, quippy speaking manner. By the end, he’s as emotionally shattered as his great opposite number, vowing never to fight another battle. And he didn’t. Waterloo marked Wellington’s final military campaign. A career in politics and the post of British Prime Minister were to follow.

The film was a colossal flop, a costly exercise in expansive, epic caprice covering a topic that the public had little interest in seeing. Director Sergey Bondarchuk had previously directed an adaptation of War and Peace, a Russian language version that isn’t to be confused with King Vidor’s massive affair from the 1950s. The 1965 take came in at a colossal length of around seven and a half hours, and won the Oscar for best foreign language film, and it was presumably this, and his ability to shoot enormous battle sequences, which made him an obvious choice for Waterloo. But whereas War and Peace is a sweeping romantic saga beyond the war scenes, Waterloo is about nothing other than the battle itself. While this has worked elsewhere, Zulu for example, it struck no chord with audiences whatsoever.

Does this make it a bad movie? For me, I would say not. Though it weaves a famous story about which everyone knows the outcome, and while some of the film’s occasional moments of humour are more than a little forced, its faithfulness to historical fact, enormous scope and the tension of battle make up for any shortcomings. To see Waterloo recreated, at the sort of scale that could only be replicated now using CGI, and the involvement of tactics and their outcomes, allied with the confusion and brutality of pitched battles, is dizzying stuff. Steiger and especially Plummer are the only real performances of note. Orson Welles turns up for little more than a cameo, and there are similarly fleeting roles for the likes of Michael Wilding, Ian Ogilvy and Virginia McKenna. Jack Hawkins appears, speaking nothing like he traditionally did, an unfortunate consequence of life-saving surgery that had removed the actor’s larynx, leaving his lines to be dubbed. The principles are both good however, lending authentic notes to real people , and the battle itself is quite like nothing else seen on the screen. Simply to see a filmed conflict where the armies do more than just charge at each other and the bravest wins, where strategic decisions are made and have real consequences, is a real treat. There’s intelligence here, and an appreciation for paying honour to what actually happened that ought to make it worth seeing.

As mentioned above, I have put this together as part of the Christopher Plummer Blogathon, hosted by my excellent friends at Weegie Midget and Pale Writer (you can see the list of people who are involved in the Blogathon here). While these pages have been more or less left to gently ride off into the night, my film blogging spirit remains true, and I am putting together material for something new, which is intended to go beyond the limits I originally set for Films on the Box. In the meantime, thanks for reading.