When it’s on: Sunday, 14 February (8.05 am)

Channel: ITV3

IMDb Link

I’ve tried to be better at reading the classics than I am, but one title I had no trouble with was Alexandre Dumas’s The Three Musketeers. Fast paced, witty and fun, the novel never runs out of steam and its spirit was never better captured than in Richard Lester’s 1973 adaptation. It remains easily my favourite attempt at bringing the text to the screen, and does raise the question – given the material how can any film maker really go wrong?

It’s a film I have watched many times – in the early days of VCR, when I was a kid I saw it over and over – and in preparation for this piece catching it again was largely unnecessary. I still did it though, more out of pure pleasure than necessity, indeed a few happy hours were spent indulging in a double bill of this one and its immediate sequel, The Four Musketeers, which essentially gives us more of the same. It’s a well-known fact that Lester shot both movies at the same time, ostensibly deciding late in the process to split the story into two and in the process pissing off his entire cast, who would of course have earned more for appearing in separate works. Lester’s argument, that he learned part way through he had enough material to justify the split and thought the two films would work better than a more heavily edited single, held little water with his performers, who duly sued and increased their salaries. And yet, years later with all the legal wrangling long in the past and the two films remaining, it clearly stands as the right thing to do. There’s simply no bloat in either entry. Just like in Dumas’s novel, the action moves quickly and the characters are given time to become more than plot devices. George MacDonald Fraser scripted both, following the text closely and inserting moments of great comedy to augment the swashbuckling antics. Whilst two of the musketeers are less well developed than their fellows, it takes some screen writing genius to take so many persons and add flesh to their bones, where even a minor character like Spike Milligan’s cowardly husband gets to show off his chops and become a memorable presence.

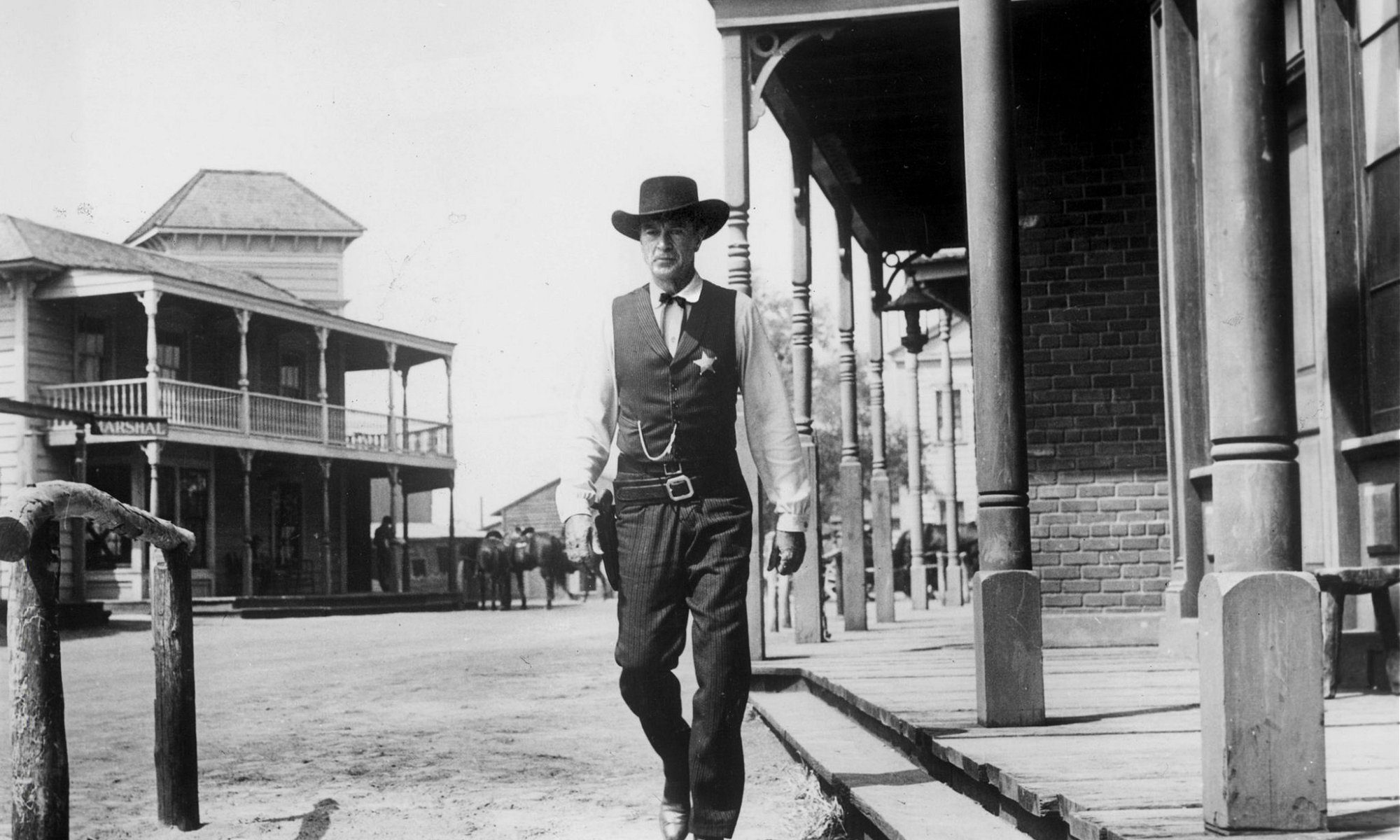

One of The Three Musketeers’ more remarkable elements is its massive ensemble cast, a seventies trend in line with the star-filled disaster movies of the time. Originally, Lester conceived his adaptation as a vehicle for the Beatles, with whom he’d famously collaborated during the previous decade, but this was obviously not an option now. The first choice for d’Artagnan was Malcolm McDowell, who would go on to demonstrate he was a match for this sort of material in Lester’s later Royal Flash, but instead the role went to Michael York, who was already a star and a perfect match for the part. York was perhaps ten years older than d’Artagnan, yet brought a great athletic dimension to bear and conveyed beautifully the character’s youthful and sometimes too hasty sense of bravado. The other Musketeers called for older heads, and they were played by Oliver Reed as Athos, Rhichard Chamberlain (Aramis) and the late Frank Finlay (Porthos). They’re introduced to the story when d’Artagnan contrives to arrange duels with all three of them, though they become friends when they find themselves engaging in swordplay with the Cardinal’s guards instead. Again, great casting. Of the trio, Chamberlain’s Aramis is left a little in the background, though he brings suitable levels of dash to his performance. Finlay is mainly on hand to play the comic and pompous relief, and he’s very, very funny (he also turns up briefly as the Duke of Buckingham’s jeweller; there’s no mistaking that voice). The real revelation comes from Reed, derided too often for his heavy drinking lifestyle but beyond that was a superb, towering and gifted performer with whom the camera was clearly in love. The pathos of Athos’s previous with Faye Dunaway’s Milady comes in the second film, but here Reed plays beautifully the tangled mess of honour, drunkenness and his fatherly relationship with d’Artagnan that defines Athos. He also brings great physicality to his fighting. Whereas York duels with an almost balletic grace, Reed plays Athos as a bullish whirlwind, using his bulk and sheer power to overcome opponents. A story from the set has Christopher Lee (having great fun as the eye-patch wearing villain, Rochefort) begging Reed to calm down during a fight sequence – it’s only a movie, after all!

Eager to extend his range after being so typecast during his Hammer era, Lee is fine as Rochefort, deadly whilst being an effete snob. He’s an unlikely partner for Milady (Dunaway), whose character becomes higher profile in the follow-up but here still gets to tease out her villain’s combination of beauty and rotten core. They both provide unsavoury service to Cardinal Richelieu, who in a rare instance of miscasting is played by Charlton Heston. He does nothing wrong in playing France’s arch-manipulator and schemer, but there’s the sense of a performer of Heston’s stature being a little subdued and underplayed. The plot works on the Cardinal’s plan to provoke war between France and England by exposing Queen Anne’s (Geraldine Chaplin) love affair with the Duke of Buckingham (Simon Ward). Once the foppish King Louis (Jean-Pierre Cassel, dubbed by Richard Briers) discovers that his wife has been unfaithful with a leading light of England’s aristocracy then conflict will surely follow. Milady travels to England to steal a couple of diamond studs from the necklace given to Buckingham by Anne, and d’Artagnan, who’s involved via assocation thanks to his burgeoning romance with the Queen’s dressmaker (Raquel Welch, showing good comic timing and adorability as a haplessly clumsy heroine), follows to resolve the situation.

That’s the story, and it’s one deftly told, but what remains in the mind are the fun performances, moments of good natured humour (the likes of Milligan, Roy Kinnear and Bob Todd are on hand to raise the film’s comedy levels) and sword fights. The latter are nicely done, deftly edited, Lester filming simultaneously from long shots and in close-ups and handing real swords to his actors to add to the authenticity. This led naturally to a variety of injuries suffered by the cast; few escaped from the shoot unscathed, and Reed took a rapier point in his wrist at one stage. With all this going on, it’s easy to ignore the attention to detail that’s going on all the time. The characters in The Three Musketeers might come with modern sensibilities and dialogue, but they’re dressed very well, and the locations – it was filmed in a variety of places across Spain – look suitably ravishing. Michael Legrand’s sumptuous score is a further bonus. This wasn’t among the many Oscar nominated pieces of work he submitted over the course of a highly successful career, but it’s a lovely musical accompaniment and does well to keep pace with the tenor of the action.

The Three Musketeers put in regular appearances across the TV schedules, and I’m surprised if there’s anyone who hasn’t seen it at least once. All the same it’s ever a welcome presence, and it effortlessly bounds over the films released in 1993 and 2014 that both squandered the richness of the source material they were working from.

The Three Musketeers: *****