When it’s on: Friday, 15 June (9.00 pm)

Channel: More4

IMDb Link

One of the nicest side-effects of the DVD revolution is the opportunity to watch ‘director’s cut’ editions of our favourite films. Often enough, this translates into some footage that didn’t quite make the theatrical version being shoehorned in, presumably whether the director’s had anything to do with it or not, but that’s fine with me. You want me to have an extra forty minutes of a Lord of the Rings movie? Don’t mind if I do.

I can’t think of anyone who’s done more director’s cuts than Ridley Scott, whose every work appears to be the subject of a revised edition at some point. The notorious example is, of course, Blade Runner, and the five-disc copy I own. Blade Runner’s a great film, but in fairness I don’t need umpteen different versions of it. To date, I haven’t cued up the workprint on the fifth disc, and I can’t imagine ever feeling the need to do so. Enough Deckard. More than enough ships on fire off the shoulder of Orion. Too much of the bloody paper unicorns. And, you know what, I didn’t mind the narration…

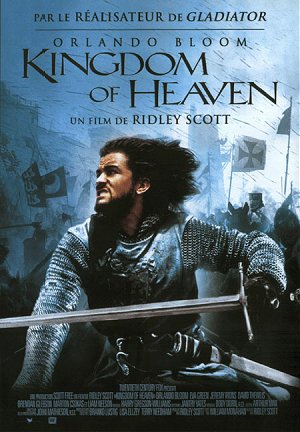

Scott’s reached a point now where one expects the director’s cut; I recall Robin Hood being released on DVD as an extended director’s edition, as though just to get it out of the way. And then there’s Kingdom of Heaven, my personal nomination for the film that’s been most improved following the addition of 48 minutes’ worth of extra material. In fact, I would go on to suggest that the director’s cut is the best of the ‘revival epics’, an outstanding piece of work on both a technical and narrative level that fleshes out its characters, provides a better historical context and throws in extra lashings of medieval tragedy.

It’s worth noting what a bold movie Kingdom of Heaven was to begin with. Much was made upon its release of writer William Monahan’s attempts to produce a screenplay that wouldn’t offend twenty first century viewers – in fact, it’s a script that appears fairly true to its most controversial character, Ṣalāḥ ad-Dīn Yūsuf ibn Ayyūb, or Saladin, the Sultan who is treated in the film as a towering figure of nobility and enlightenment. The Knights Templar, the other hand, emerge as its villains, the epitome of boorish Westerners on the make and in the ‘Holy Land’ for whatever they can take from it.

Also brave is the decision to make a serious film about the Crusades at all. Most people know basically what the Crusades were (though when I was at school, it was discretely airbrushed out of our History lessons), and there have been some very good documentaries on the subject, not least this recent series from the BBC. Less is known of the era’s politics, its various and ongoing tensions between contemporary factions. Kingdom of Heaven takes as its subject a real moment in history, the events leading up to and including Saladin’s recapture of Jerusalem. In order for it to make any sense, it has to explain everything – the various characters, their motivations and the broader historical narrative. That’s a lot for it to do, and a major job to get all this on the screen without sounding like a lecture. On the whole, both versions of the film succeed, though the director’s cut, with its padding, does a much better job of putting across all the necessary information.

The one character radically altered from historical reality is the film’s main focus, Balian of Ibelen, played in the film by Orlando Bloom. Actually a noble, in Kingdom of Heaven he starts as a blacksmith in some medieval French village, clawing out a living in a land pockmarked by death, dirt and disease. Lamenting the suicide of his wife, Balian’s life changes with the arrival of Baron Godfrey (Liam Neeson), returning briefly from Ibelin with the intention of finding his bastard son, who turns out to be none other than Balian himself. Godfrey gives Balian the opportunity to join him in the east, an offer that’s rejected initially but after the latter murders his brother, a corrupt priest played by Michael Sheen, he sees in Godfrey the chance to atone for the sin of his wife’s suicide by becoming the best of knights in the Holy Land. Soon enough, he enters Jerusalem and takes his place on the canvas of Middle Eastern politics as the leprous King Baldwin (Edward Norton, wearing a mask throughout the film) tries to keep the uneasy peace between Christians and Muslims, both placating Saladin’s vast army and keeping at arm’s length the ambitious Templar, Guy de Lusignan (Marton Csokas).

Everything you need to know about Balian is in the saying carved into a beam of his blacksmith’s shop – What man is a man who does not make the world better? Orlando Bloom, at the height of his fame when cast in the film, was handed the difficult job of making his character both credible and inspirational. He had to carry a huge movie on his shoulders and duly gained weight for the part, appearing muscular and doing all he could to shrug off the ‘pretty boy’ catcalls that were becoming the stock criticism of his talent as an actor. These were based in no small part on his performance in the first Pirates of the Caribbean film, in which he was handed the wooden, callow role whilst Johnny Depp got the best lines and Keith Richards impersonation. In the director’s cut of Kingdom of Heaven, his expanded scenes show what a fine performance he actually put in. Capable of carrying the story and featuring in scenes – excised from the theatrical version – that demonstrate Balian’s ability to inspire and lead, there’s nothing at all wrong with his acting. Unfortunately, the shorter edition of Kingdom of Heaven that made it into theatres left a lot of this stuff on the cutting room floor, giving us in turn a truncated Balian who feels caught up in the tumultuous events in which he happens to have been dropped.

It’s an important point. If viewers don’t believe in Bloom’s Balian, then much of what makes the film work is lost. It becomes a tale about people in whom we can’t invest. Worse still than Bloom is the treatment dished out to Eva Green. Playing Baldwin’s sister, Sibylla, in the theatrical cut she comes across as little more than a medieval slapper, falling for Balian yet betrothed to Guy and handing him the kingship when Baldwin succumbs to his illness. What’s lost is her character’s entire background, which forms a small but vital sub-plot restored in the director’s cut. Without this, it’s difficult to see a point to Sibylla and certainly there seems little motivation in the ‘in shock’ character she has become by the film’s close.

Elsewhere, there are memorable turns from Brendan Gleeson, as Guy’s boorish henchman, and Jeremy Irons as a cynical Knight Hospitaler who exists to despair over the loss of mission to the Christian occupation of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Both characters are as fine in the theatrical version as they are in the expanded edition. David Thewlis has a neat supporting role, and Ghassan Massoud is the epitome of assiduous nobility as Saladin. Kingdom of Heaven has a wealth of famous names popping up in minor roles – Kevin McKidd, Alexander Siddig, Philip Glenister, Nikolaj Coster-Waldau and Iain Glen (indeed, by coincidence, much of the cast of Game of Thrones appears in some shape or form), and small, crucial roles for Bill Paterson and Robert Pugh ended up being cut.

But where both versions of the film really come into their own is in the visual sense. Always capable of producing ravishing ‘looks’ for his films, Scott places Kingdom of Heaven within a historical setting that appears so authentic he might as well have invented a time machine in which to send his cast and crew back into the twelfth century. The two major battles look incredible and it’s practically impossible to tell where the human actors finish and the CGI takes over. The best shot, that of the Christian forces appearing on the horizon at a critical moment, really is superb, particularly the sight of an enormous cross glistening in the sun. That apart, the costumes and design work take some beating. I recall a comment about Scott’s Robin Hood in which it was wished that the film could have been anything like as good as the effort plunged into the way it looked. Kingdom of Heaven is every bit as lustrous. One of the closing shots, which depicts Saladin striding through Jerusalem’s former cathedral, Christian flags falling to the floor around him, demonstrates just how much attention has gone into the detail throughout. Only it’s better than Robin Hood because the plotting is so rich in detail and layers. I’d go so far as to argue that the director’s cut is an improvement on Gladiator, only it had the misfortune to be made later.

Sadly, the version screened in cinemas is the one scheduled by More4. It’s still a powerful piece of work, though the rushed story of certain characters and loss of subtlety makes it a film that isn’t always easy to follow. The politics are too complicated and the level of characterisation all too uneven. Yet the early part of the film, the scenes set in France, are wholly immersive and it’s only later, once Balian takes the route where people speak Italian until they speak something else, that it starts to lose its way.

Kingdom of Heaven: ***