When it’s on: Wednesday, 9 May (1.55 am, Thursday)

When it’s on: Wednesday, 9 May (1.55 am, Thursday)

Channel: Channel 4

IMDb Link

A real guilty pleasure this, reminiscent of a lost childhood spent watching old Tarzan and Charlie Chan movies on BBC2, not to mention the Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers serials the same channel churned out to pad its early evening schedules. Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow groans under the weight of its own charm, its recapturing of not just a film-making era from seventy years previously, but also its look and style. Gwyneth Paltrow’s character comes straight from the pages of ballsy, 1930s heroines who gave as good as they got. Her verbal sparring with Jude Law has real sparkle, which almost matches the visual magic director Kerry Conran shoehorns into every scene.

It’s a terrific film, unfairly lambasted upon its release during the CGI backlash of the era. Whereas there are certainly instances of narrative, acting and urgency being lost amidst all that green screen filming (the Star Wars prequels come to mind here), Sky Captain is a cut above because every element has been considered carefully and works. I wrote a critique of it after being blown away during a cinema visit back in 2004 and, reading it now, I see no reason not repost the entire piece in full.

—

So what’s it to be? Computer generated imagery gone mad, or an evolutionary step in movie making? Is Sky Captain a curiousity, a visually mind-blowing experience but without a soul? Or does it keep its heart, marrying those lovely effects with a sizzling plot, good acting and pace? In short, is there room in this world for a picture where everything is filmed before the now infamous green screen, all the backgrounds, sounds, planes, killer robots and monsters added later?

The story behind Sky Captain’s making is the stuff of painstaking legend. A-list stars like Jude Law and Gyneth Paltrow were recruited to strut their stuff before the screen, using markers to interact with things that weren’t there. Once all that was done, the computer effects were added. Pretty much everything apart from the actors themselves was fake, generated by technology, and the reason for this? Sky Captain is set in the late 1930s, and looks like a movie made in that time too. The colours are muted. Visual trademarks, like a camera scaling the side of a skyscraper, or the characters flying some distance represented by a map covering the ocean below, are pure era stuff. The baddies – early in the film, New York is invaded by giant robots with single white lenses for eyes – appear as though they belong in this time. Milk of Magnesia is used to cure flying sickness. People go to the cinema, a grand, art deco affair with swishing curtains, and see The Wizard of Oz.

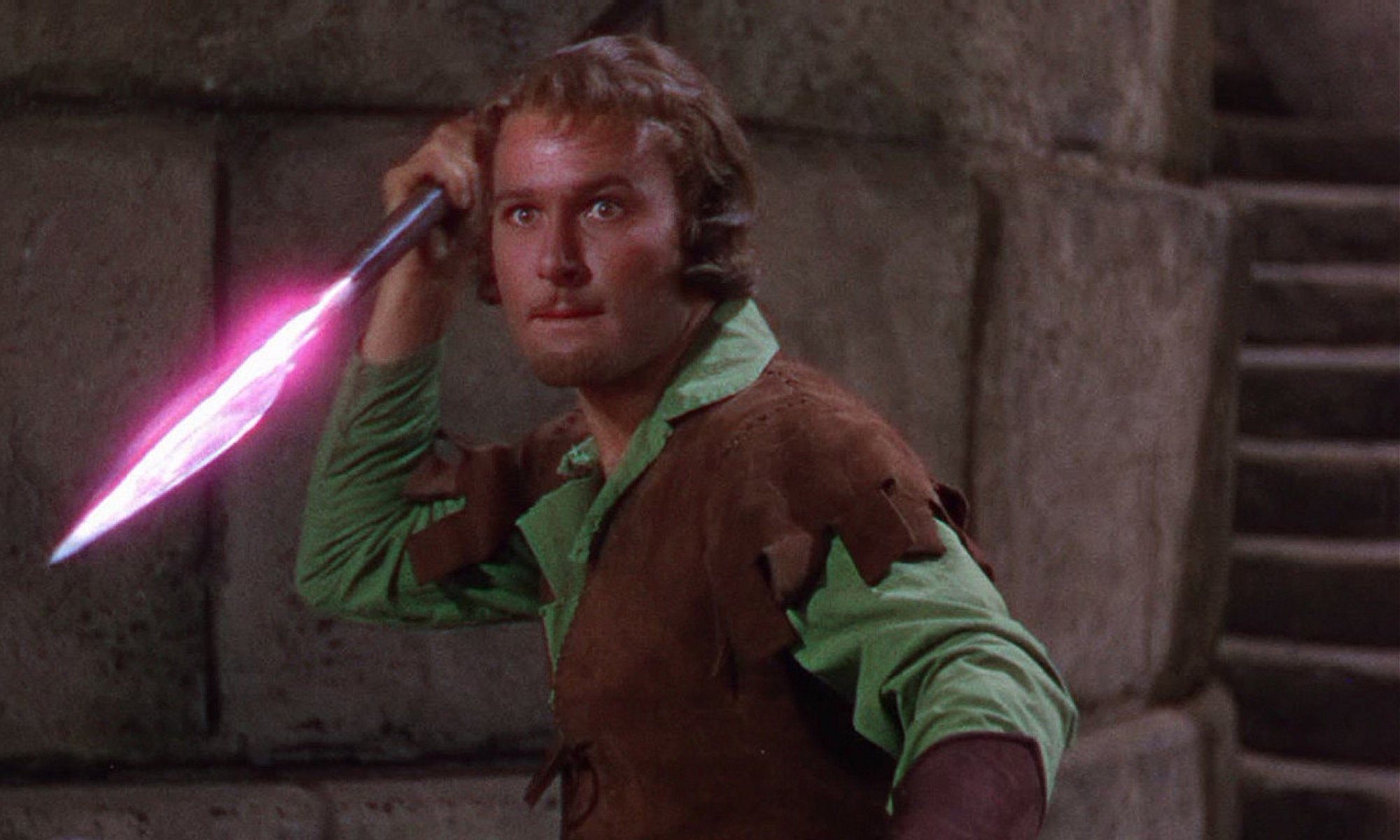

Sky Captain is played by Jude Law, who’s made for this this sort of caper. A Biggles type, square-jawed fighter pilot, he uses a variety of souped-up weapons in his improbable jet to combat the robots. Later, having collecting Polly (Paltrow, with whom he has had some previous) the pair find out more about the robot attack via a visit to the Himalayas, getting some help from Angelina Jolie as the commander of a floating aircraft carrier* and end up on a secret island… the home of… what, exactly?

The plot complements the extravagant look of the picture perfectly. The leads, Law and Paltrow, are perfect, particularly the latter who embodies the brassy, salty 1930s heroine with natural ease. Her interaction with Sky Captain sizzles, a couple who still have feelings for each other and hide it behind sarcastic wisecracks and anatagonism. Even better are the scenes with Jolie. Not only does she get to be in charge of one of those amazing vessels in the clouds (complete with Union Jack insignia on the side), but she also wears an eye-patch and leads her own fleet of planes.

This is a movie that has been accused of lacking substance, of being all about the visuals. Sure enough, the effects are fabulous. Sky Captain looks unique, with its retro setting and a genuine attempt to create contraptions as they would be imagined by 1930s film makers (other nice touches include the Captain’s boffin friend, Dex (Giovanni Ribisi), tracking the location of the secret island with the use of a wireless, ruler and stencil equipment), but it’s much more than that. Clearly, Paltrow and Law have chemistry, and as they’re in most frames together, we get to see an excellent use of a couple who are equal partners rather than the hero and his babe. It’s got humour, pace and suspense in equal measures. All involved are happy enough both to send up their roles through playing it straight, and look like they’re having a good time in the process. Heck, there’s even a posthumous appearance by Laurence Olivier, his scenes cobbled together from archive footage.

That said, Sky Captain is ultimately a forgettable experience, a treat for the senses that flashes by easily enough and never taxes the brain. But didn’t they say that about the Indiana Jones films, which this most resembles in spirit? When Spielberg and Lucas turned Harrison Ford into a tomb-raiding adventurer, they set out to make the archetypal matinee experience. And that’s just what this feels like. Just like Raiders of the Lost Ark, it’s an absolute blast. Incidentally, the golden age of the matinee was the 1930s, and as it goes, Sky Captain has the look and feel of a movie that was made by thirties producers who suddenly found themselves with access to modern technology.

Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow: ****

*Good to see that airborne aircraft career idea pop up again, first as the Valiant in Doctor Who, and more recently in Avengers Assemble. There’s sure no keeping a good concept down!